If a uniform

Africa can be widely discussed within literature, why has it never been

actualised?

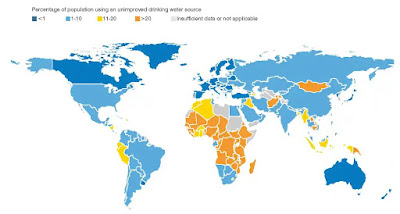

Taking this to a greater extreme, why isn’t water experienced

equally across the globe?

Generally, the notion of the less developed world being especially vulnerable to water

problems and all those that spew out of it is common knowledge.

So why don’t these regions resemble the west – extraordinarily, even in the 21st

Century?

Not to

take away the power from fundamental physical geography factors that inevitably

organise and allocate water sources, but this is one common element that cannot

be rewired. Instead, to uncover explanations for Africa’s current climate, we

must retrace its history.

Colonialism. Aspects of capitalism, exploitation,

and greed are rooted in it. Centrally, associations of power imbalances. Perhaps

a more advantageous question to raise would be of why intra-African disparities

and conflicts exist in a postcolonial world. Ideas of solidarity would logically bind depleted African nations in the aftermath of colonialism, so why then is this not the case?

The History:

|

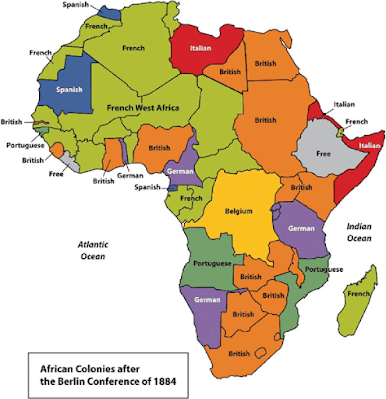

| Figure 2: A French caricature depicting German chancellor Otto von Bismarck dividing the African continent amongst colonial powers.

|

The uniform territorialisation of Africa is evident in the artificial looking shapes of its countries.

Africa vs The West

On a broad scale, the age of imperialism in Africa exercised a theft of its natural resources. Gold, palm oil, metals, diamonds - very much a curse than a blessing. Removal of a primary source of wealth resulted in a lack of economic stability and funding to deliver the infrastructure required to collate and distribute water.

Moreover, the accumulation through dispossession motive set the foundations for existing inequalities. The cities of Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, and Mombasa exemplify how colonial organisation guaranteed future problems of inequality and backwardness for African countries. Land redistribution and zoning used to provide for colonial settlers and separate them from natives created infrastructural frameworks designed to racially discriminate. Water allocations permitted 220 litres per day to non-natives, and only 45 litres to Africans in Nairobi. Africans were seen as labour, and forced into informal settlements subject to precarious water access while the elite enjoyed piped water in Dar es Salaam. The notion of 'dual economy' reflects the disparity between the relegated locals and serviced masters (Palmer and Parsons, 1977). A racism that underlines inherent underdevelopment and the politicisation of basic water provision services. Intra-Africa Relations

Residues of imperialism are further reflected in the power relations that govern water. Histories of treaties and political backing by colonial powers favouring advantageous regions carry forward into the power imbalances of today. The British Nile is a long standing example of how Britain's favouritism towards Egypt has historically granted it greater power over the Nile in comparison to other riparian countries. The ability to influence long term conflict through 'legal' frameworks/treaties/political support, means that even physically advantaged states (like upstream Ethiopia) are subject to division and conflict with their neighbours - colonialism dictated allocations of power.

Final Thoughts

Through this blog I have discovered a newfound importance attributed to historical backgrounds that inevitably determine the present. By situating concerns within wider global structures, and assessing the power relations that play out, an accurate image of the postcolonial world is formed - a great start for discussing the future.

You have demonstrated a sound grasp of water issues in Africa with insights into broader implications, and engagement with relevant literarure. The referencing is good in the introductory post but was inconsistent in the second post, also the two posts did not build upon one another beyond the notion of colonial history. Bringing in some specific case studies will be helpful, one you have already alluded to is the Nile basin.

ReplyDelete